|

| Joseph Mallord William Turner, The Wreck Buoy, 1849, oil on canvas (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool) |

Sunday, August 28, 2011

Saturday, August 27, 2011

Leonardo's Deluge

|

Leonardo da Vinci, A Deluge, c.1517-18, Black chalk, 15.8 x 20.3 cm (Probably acquired by Charles II; Royal Collection by 1690, RL 12377). More of Leonardo's deluge drawings can be found here. |

Sunday, August 21, 2011

More Art News

By Charles Kessler

LINKS:

EXHIBITIONS:

Breaking Ground: The Whitney’s Founding Collection (Until September 18, 2011).

I went to the Whitney mainly to see their comprehensive Lyonel Feininger exhibition so I was surprised to come across this delightful show — a selection from the more than 1000 works of the original Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney collection. (BTW, even though I’m not a great fan of Feininger, I learned there’s more range and depth to him than I realized.)

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was staggeringly rich even by the standards of today’s billionaires. She was the daughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt II, the richest man in America at the turn of the century, and the wife of Harry Payne Whitney from one of New York’s wealthiest families. Defying her background, she became a sculptor, and not a bad one as you can see from this photo (above). Perhaps more important in terms of her place in history, she was a major patron of contemporary American art at a time when American art was ignored.

The exhibition attempts to capture the look of the original museum and the democratic approach to collecting and installing — salon style with a diversity of subjects, styles and quality. (The Studio School took over the building, and the original Whitney Museum entryway, lobby and several rooms on the first floor - now used for the school's gallery - are still pretty much intact and are open to the public.)

One of my favorite paintings in the exhibition is by the under-appreciated painter Louis Eilshemius.

Governor’s Island is worth a trip in itself. You have to take a ferry there (click here for the schedule)

so you feel like you’re on summer vacation somewhere. It’s a verdant island with historic old residential homes once used by naval officers. They even have a beach with a volleyball court, a bandstand and a hamburger shack.

The show is the largest outdoor presentation of di Suvero’s sculpture since the 1970s — 11 sculptures created over a period of 40 years and spread out over the 172 acres of Governors Island.

These are big sculptures, some 16 feet tall, but they never feel imposing or oppressive the way Serra’s work often does. Rather they are human in scale and even intimate in their way. De Suvero had a good point with regard to the height of his works: “Forty-story buildings are being torn down in New York so that sixty-story buildings can go up. Why are people so surprised at seventeen-ton sculpture?”

Storm King developed a free app to accompany the exhibition. It’s particularly useful since no map is provided and you really need something to locate the sculptures.

BMW Guggenheim Lab, at the corner of Second Avenue and Houston in the Lower East Side (Until October 16, 2011).

This isn’t an exhibition so much as a city-planning science museum. It’s purported goal is to get ideas from people about what makes a city livable, but, so far at least, it’s more didactic than that, and probably more interesting because of it. They will have lectures, films and various events, including games (like the one shown above), about the needs, trade-offs, and challenges of cities.

The "lab" is housed in a temporary space designed by the Japanese architects Atelier Bow-Wow. Made of carbon pillars and carbon fiber and open front and back to the street and air, it's more of a high-tech tent than a building. Practicing what they preach about livable cities, they provide a nice amenity -- a plywood food shack run by Roberta's, Bushwick's popular pizza restaurant.

This will be a long-term experiment. After they finish here, they'll pack up and take the show on the road to Berlin, Mumbai and several other cities.

A quick note about "artist/philosopher" (the curator Alexandra Munroe's designation) Lee Ufan exhibition in the Guggenheim's uptown space. It is precious beyond belief. It's embarrassing in its pretentious artiness, and it's appallingly derivative. This is a bad show even in comparison to the recent run of bad Guggenheim shows. "Artist/philosopher" indeed!

Rembrandt and the Face of Jesus, Philadelphia Museum of Art (Until October 30, 2011).

The show is a bit of a rip-off. The show should be called The Face of Jesus: a few Rembrandt paintings, drawings and prints and a lot of paintings by his pupils. And it costs $16 general admission and an additional $9 for the “Rembrandt” exhibition — $25 total. There are a few major works, though, that for me were worth the price of admission. I particularly liked seeing two of Rembrandt's famous “100 Guilder Prints” side by side so I could observe how Rembrandt wiped the plate in different ways to bring out different features of each print. And there was this profoundly moving painting:

And finally, I noticed a strange phenomenon at MoMA and I wonder if you may have noticed it too. Almost always, on one side of a wall between galleries the art is wildly popular, while the opposite side is practically deserted.

Okay Van Gogh's Starry Night is famous, but Picasso’s Three Musicians isn't. And Cezanne's Bather and the Brancusi sculptures completely shunned? What's with that?

LINKS:

- Via the art blog Two Coats of Paint, I learned of this video (below) about Hans Hofmann’s legendary art classes in Provincetown. It contains interviews with many of his former students including Mercedes Matter and Red Grooms, and archival video and photos of his classes.

- If you don't want to spend $75 or $100 or more on a western art history textbook, especially since it won't even have very many good reproductions let alone videos narrated by some of the top people in the field, smARThistory.com's free art history "web-book" is for you.

Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker, the founders of smARThistory, say they have "aimed for reliable content and a delivery model that is entertaining and occasionally even playful. Our podcasts and screen-casts are spontaneous conversations about works of art where we are not afraid to disagree with each other or art history orthodoxy." I checked out a sampling and agree.

- For some striking large-format photojournalism, check out The Big Picture: New Stories in Photographs, on the Boston Globe’s website.

EXHIBITIONS:

Breaking Ground: The Whitney’s Founding Collection (Until September 18, 2011).

I went to the Whitney mainly to see their comprehensive Lyonel Feininger exhibition so I was surprised to come across this delightful show — a selection from the more than 1000 works of the original Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney collection. (BTW, even though I’m not a great fan of Feininger, I learned there’s more range and depth to him than I realized.)

|

| Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, Chinoise, 1914. Limestone, 61 1/16 × 19 15/16 × 14 7/8 inches (Whitney Museum of American Art; gift of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney 31.79). |

|

| The original Whitney Museum of American Art at 10 West 8th Street, c. 1931-3. |

One of my favorite paintings in the exhibition is by the under-appreciated painter Louis Eilshemius.

|

| Louis Eilshemius, The Flying Dutchman, 1908, oil on composition board, 23 1/2 x 25 1/2 inches, (Gift of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney). |

Mark di Suvero at Governors Island, presented by Storm King Art Center (until September 25, 2011).

|

| Governors Island, New York |

so you feel like you’re on summer vacation somewhere. It’s a verdant island with historic old residential homes once used by naval officers. They even have a beach with a volleyball court, a bandstand and a hamburger shack.

|

| Governors Island Beach |

|

| Mark di Suvero, Fruit Loops, 2003, Steel, 16’ 4” x 15’ x 11’ 7” (Collection of Agnes Gund, New York). |

Storm King developed a free app to accompany the exhibition. It’s particularly useful since no map is provided and you really need something to locate the sculptures.

BMW Guggenheim Lab, at the corner of Second Avenue and Houston in the Lower East Side (Until October 16, 2011).

This isn’t an exhibition so much as a city-planning science museum. It’s purported goal is to get ideas from people about what makes a city livable, but, so far at least, it’s more didactic than that, and probably more interesting because of it. They will have lectures, films and various events, including games (like the one shown above), about the needs, trade-offs, and challenges of cities.

The "lab" is housed in a temporary space designed by the Japanese architects Atelier Bow-Wow. Made of carbon pillars and carbon fiber and open front and back to the street and air, it's more of a high-tech tent than a building. Practicing what they preach about livable cities, they provide a nice amenity -- a plywood food shack run by Roberta's, Bushwick's popular pizza restaurant.

This will be a long-term experiment. After they finish here, they'll pack up and take the show on the road to Berlin, Mumbai and several other cities.

|

| Roberta's at the BMW Guggenheim Lab. |

Rembrandt and the Face of Jesus, Philadelphia Museum of Art (Until October 30, 2011).

The show is a bit of a rip-off. The show should be called The Face of Jesus: a few Rembrandt paintings, drawings and prints and a lot of paintings by his pupils. And it costs $16 general admission and an additional $9 for the “Rembrandt” exhibition — $25 total. There are a few major works, though, that for me were worth the price of admission. I particularly liked seeing two of Rembrandt's famous “100 Guilder Prints” side by side so I could observe how Rembrandt wiped the plate in different ways to bring out different features of each print. And there was this profoundly moving painting:

|

| Rembrandt van Rijn, Christ with Arms Folded, ca. 1657-1661, Oil on canvas, 43 x 35 1/2 inches, (The Hyde Collection, Glens Falls, New York, 1971.37) Photograph by Joseph Lev. |

Okay Van Gogh's Starry Night is famous, but Picasso’s Three Musicians isn't. And Cezanne's Bather and the Brancusi sculptures completely shunned? What's with that?

Friday, August 19, 2011

Bushwick News

By Charles Kessler

Most young artists coming out of art school can’t afford Williamsburg anymore, so for the last five or ten years artists have been flocking further east to Bushwick. For the moment, Bushwick's run-down warehouses are more affordable because there are still vestiges of gang activity, few trendy restaurants and bars (Roberta’s, 261 Moore Street near Bogart Street, being the most noted exception), and a somewhat longer commute to Manhattan.

The galleries are spread out over the two-mile neighborhood, but they’re coalescing more and more around the Morgan Avenue L train stop where there are about a dozen of them. The prominent nonprofit arts organization Nurture Art will be moving into this area, joining Momenta Art, a recent Williamsburg transplant, and a couple of other art galleries -- all in the same building at 56 Bogart Street. Nurture Art hopes to open in October.

A bigger surprise is that the blue-chip Chelsea gallery Luhring Augustine will open up a 12,000-square-foot space at 25 Knickerbocker Avenue in Bushwick, also near the Morgan Avenue L station. Artist/filmmaker/dance documentarian Charles Atlas will be their first exhibition.

PLEASE NOTE: MOST OF THE GALLERIES ARE CLOSED FOR THE SUMMER. In the fall I’ll post a map and guide to the Bushwick art galleries similar to our Guide to the Lower East Side Galleries.

|

| Bushwick is toward the top of the map, in maroon. |

Most young artists coming out of art school can’t afford Williamsburg anymore, so for the last five or ten years artists have been flocking further east to Bushwick. For the moment, Bushwick's run-down warehouses are more affordable because there are still vestiges of gang activity, few trendy restaurants and bars (Roberta’s, 261 Moore Street near Bogart Street, being the most noted exception), and a somewhat longer commute to Manhattan.

The galleries are spread out over the two-mile neighborhood, but they’re coalescing more and more around the Morgan Avenue L train stop where there are about a dozen of them. The prominent nonprofit arts organization Nurture Art will be moving into this area, joining Momenta Art, a recent Williamsburg transplant, and a couple of other art galleries -- all in the same building at 56 Bogart Street. Nurture Art hopes to open in October.

A bigger surprise is that the blue-chip Chelsea gallery Luhring Augustine will open up a 12,000-square-foot space at 25 Knickerbocker Avenue in Bushwick, also near the Morgan Avenue L station. Artist/filmmaker/dance documentarian Charles Atlas will be their first exhibition.

|

| The new home of Luhring Augustine Gallery, photo courtesy of mercurialn via Flickr and ARTINFO |

Monday, August 15, 2011

A Fleeting Impression

By Kyle Gallup

Today my world is black, white and gray. I’m kept company by an image of a single, mercurial cloud hanging in the summer sky and hovering above buildings silhouetted by an overhead sun that makes every edge feel razor sharp.

I’ve begun working on a series of altered prints, images of a sunny view outside my studio window. Drawing on top of the prints with pencil, I intend to change the character of each print by building up the surface and creating a quiet, visual drama in each one. Retreating into my dark, book-lined room, I’m set up on a long, craggy table. Sequestered from the outside, I hope to find some peace of mind in the process.

While working I’m watching an early episode of the 1960’s TV show “The Fugitive.” I’ve taken to this program, obsessed with it and the idea that a man on the run with little more than the clothes on his back and a few dollars in his pocket can survive.

It’s 1964 and America feels different than today. The small towns, filmed in black and white, which Dr. Richard Kimble passes through, have main streets with mom & pop stores, huge cars, and children playing in the streets. A person wanting to lose himself, hide or find a job can easily thumb a ride into town for a couple of weeks and then be on his way.

While listening to and considering the dangerous situations that Richard Kimble finds himself in I take time to build up graphite on the paper. It’s slow going and my pencils need to be sharpened every few minutes to give me as much control as possible. With the porous, soft material I create depth and density. I especially like the feeling of rubbing the steely-colored dust with my fingers, making the darks as black as possible.

Thoughts of temporality run through my mind, as I consider how a single cloud can take shape and change form many times over, positioning and repositioning in the vastness of the sky. This floating presence has a relationship to the buildings around it making it feel organic and weightless. The cloud’s fleeting, rootless character is captured by my use of technical means—its identity caught for posterity in a diaphanous, bright white in my final drawing.

I can bear to watch Richard Kimble endure hiding out, getting double-crossed, captured, and escaping again and again because I trust that at the end of his journey he will find what he’s looking for—the one-armed man who murdered his wife. He will finally be set free from the pain and desperation that have plagued him for so long. I watch David Janssen’s solid, subtle, truth-filled performances without disbelief even while I doubt that a fugitive today could hop a freight, assume many aliases, and persuade people of his innocence.

Though our lives are constantly in flux, I take comfort in the thought that as quickly as a cloud passes across the sky, a man on the run can find momentary refuge. The message is simple: change carries a particular kind of freedom and can be expressed and accepted as an end in itself. The key? Living and creating in the moment.

Kyle Gallup is an artist who works in collage and watercolor.

Today my world is black, white and gray. I’m kept company by an image of a single, mercurial cloud hanging in the summer sky and hovering above buildings silhouetted by an overhead sun that makes every edge feel razor sharp.

I’ve begun working on a series of altered prints, images of a sunny view outside my studio window. Drawing on top of the prints with pencil, I intend to change the character of each print by building up the surface and creating a quiet, visual drama in each one. Retreating into my dark, book-lined room, I’m set up on a long, craggy table. Sequestered from the outside, I hope to find some peace of mind in the process.

While working I’m watching an early episode of the 1960’s TV show “The Fugitive.” I’ve taken to this program, obsessed with it and the idea that a man on the run with little more than the clothes on his back and a few dollars in his pocket can survive.

It’s 1964 and America feels different than today. The small towns, filmed in black and white, which Dr. Richard Kimble passes through, have main streets with mom & pop stores, huge cars, and children playing in the streets. A person wanting to lose himself, hide or find a job can easily thumb a ride into town for a couple of weeks and then be on his way.

While listening to and considering the dangerous situations that Richard Kimble finds himself in I take time to build up graphite on the paper. It’s slow going and my pencils need to be sharpened every few minutes to give me as much control as possible. With the porous, soft material I create depth and density. I especially like the feeling of rubbing the steely-colored dust with my fingers, making the darks as black as possible.

Thoughts of temporality run through my mind, as I consider how a single cloud can take shape and change form many times over, positioning and repositioning in the vastness of the sky. This floating presence has a relationship to the buildings around it making it feel organic and weightless. The cloud’s fleeting, rootless character is captured by my use of technical means—its identity caught for posterity in a diaphanous, bright white in my final drawing.

I can bear to watch Richard Kimble endure hiding out, getting double-crossed, captured, and escaping again and again because I trust that at the end of his journey he will find what he’s looking for—the one-armed man who murdered his wife. He will finally be set free from the pain and desperation that have plagued him for so long. I watch David Janssen’s solid, subtle, truth-filled performances without disbelief even while I doubt that a fugitive today could hop a freight, assume many aliases, and persuade people of his innocence.

Though our lives are constantly in flux, I take comfort in the thought that as quickly as a cloud passes across the sky, a man on the run can find momentary refuge. The message is simple: change carries a particular kind of freedom and can be expressed and accepted as an end in itself. The key? Living and creating in the moment.

|

| Kyle Gallup, Cloud #1, 2011, 11 x 15 inches, graphite on lithographic print on paper. |

Kyle Gallup is an artist who works in collage and watercolor.

Monday, August 8, 2011

Curatorial Flashbacks #15: Early Daze

By Carl Belz

My first encounter with the museum profession had me writing a few paragraphs for the brochure of a modest Man Ray exhibition at the Princeton University Art Museum in the spring of 1963. I’d earned my doctorate earlier that year with a dissertation on Man Ray’s contribution to Dada and Surrealism and, armed with a BA, MFA and PhD, all from Princeton, I was about to set off to my first teaching job, at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst.

I came upon Man Ray through surveys of Dada and Surrealism I read while preparing for my qualifying examinations during spring semester 1962. He was mentioned chiefly as the lone American participant in those international movements, initially in New York, where he became friends with Marcel Duchamp following the 1913 Armory Show, and then in Paris, where he moved in 1921; and he was invariably represented by the two readymade objects that remain most closely associated with his signature: the flatiron with the nails on its surface—called “The Gift”—and the metronome with its attached photo of a human eye—called “Indestructible Object.” On the lookout for a dissertation topic throughout that semester, I began to think Man Ray might be my ticket, and I was encouraged to pursue that possibility when mentor Robert Rosenblum agreed to be my adviser on the project.

Digesting the scant literature on Man Ray that existed in 1962 required little time and effort but didn’t take me very far toward building a thesis. For that, I needed primary source material, which meant going to Paris for a month, visiting with Man Ray at his studio three or four times a week, seeing work both old and new, talking at length with him about his art and artistic thought, collecting and notating images of paintings, drawings and objects provided by the Man himself and, for much of the rest of the time, making copious notes for future reference. Throughout the process, Man Ray was fully and wonderfully accommodating. Along with all of the above, he sort of took me under his personal wing, loaning me old exhibition announcements and brochures to study, occasionally inviting me to accompany him on errands around town—we ran into Yves Klein one morning—taking me to lunch a few times and, shortly before I was scheduled to return home, showing me a little snapshot that I was unaware he’d taken in which I could be seen sitting on a couch in his studio, surrounded by objects of his making, among them the memorably cosmic painting of a woman’s lips called “Observatory Time, The Lovers” and, nearby, his early mobile comprised of readymade coat hangers called “Obstruction.” I naturally coveted the photograph to document my experience but, unable to summon the audacity to ask for it, I was fully content to return home with its memory—along with what I felt were the makings of a doctoral dissertation.

Which I spent the next several months writing, rewriting and shaping into a final presentation and then readying myself for its defense. All went well, and I was especially buoyed one day toward the end of the process—which had begun to feel like a necessary rite of passage that tested not only merit but endurance as well—when I received in the mail the little photograph of myself, signed by the master, that you see reproduced here. I was momentarily baffled in not knowing where the image had come from, but I quickly remembered the studio snapshot and realized Man Ray had edited out all but a tiny fraction of the information contained in the original photograph. Wow! How could he think to do that? I was astonished by his inspiration, by the magic he’d performed, and I was in turn reminded of why I’d gone to graduate school in the first place—to learn about art’s past and the wonders of its achievement. Further, and equally important, the photograph reminded me that there were real artists out there beyond the confines of Princeton’s ivory towers, artists living lives in the here and now, all the time making new stuff that would become art’s new history. Thus did the spell over my cloistered graduate school existence begin to dissolve—and the real world begin to beckon.

Getting the PhD sounds like a smooth ride, but the back story suggests otherwise—how I was often in the dark about what I was doing during both my undergraduate and graduate years, which was mostly following my intuitions, winging it, chasing a dream of one sort or another.

For instance, I didn’t go to Princeton to prepare for advanced study in the history of art, I went to Princeton to play ball and prepare for medical school. And I did pretty well on both fronts. I was a career .300 hitter in baseball, while in basketball I helped lead our freshman team to an undefeated season (freshmen weren’t permitted to play varsity in those days), averaged double-doubles (points and rebounds) for my three-year varsity career, shot my way into the elite 1,000 point club, set that single game rebounding record I told you about in an earlier Flashback, was twice named to the starting five of the All-Ivy team, captained Princeton to a share—with Dartmouth—of the Ivy League championship in my senior year, and only once got ejected from a game (against Harvard, for fighting, grrr). In the classroom, I aced organic chemistry in my sophomore year, then became a biology major, was admitted to medical schools at Columbia University and the University of Pennsylvania in the spring of my senior year, decided on Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, and set my sights on moving to New York.

But that plan didn’t materialize, as I got seriously distracted, and eventually redirected, by art and art history. I took a drawing course with artist-in-residence Stephen Greene—he also taught a painting course, and that was the extent of art practice available at Princeton in those days, when studying art only meant studying art history—and, corny as it sounds, it turned out to be a life changing experience. While I learned that I couldn’t make particularly good drawings, I nonetheless learned awe and humility in the face of those who could, and I wanted increasingly to know more about them. So I used the handful of electives available to me in my senior year to take as much art history as I could, I became thrilled and consumed by the new world I’d discovered, and, late in the game—but not too late—I dared myself by submitting an application to stay on and pursue an advanced degree in Princeton’s Department of Art and Archaeology. Which I did.

Little did I know what I was getting into. I thought graduate study brought together a small group of people who, like me, had been blown away by art and would be spending large chunks of time talking about how great Titian and Velasquez and Pollock were. No. We were not there to learn and discuss the history of art per se—it was assumed we had already done that as undergraduates and needed only to fill in a course here and there to complete our introduction to the spectrum of western art history—we were there to learn the methods of the art historical discipline via encounters with the scholarship in which those methods were embodied. Accordingly, instead of Titian, Velasquez, and Pollock, our role models became individuals like Alois Riegl, Erwin Panofsky, and Meyer Shapiro. It took me most of my first year to figure that out, as my grades sadly attested. I got a mere “pass” in my graduate seminars, adding up to an implicit suggestion that I think twice about continuing in the program. Fortunately, I was still too naïve to read that writing on the wall.

I was, however, fully able to grasp what the writing said about the financial situation I would face in my second year, when my fellowship would be reduced to tuition alone—it said I’d better find work pronto! That’s when my undergraduate experiences began to pay off. Based on the lab skills I’d learned in science courses, I landed a job with a small chemical research firm in town, which I worked fulltime during the summer of 1960 and was able to continue on a part time basis once the academic calendar resumed in the fall. By that time, I’d also earned a spot playing professional basketball on Saturday and Sunday nights—and earning $50 a game—for the Scranton Miners of the Eastern Basketball League, which served as a breeding ground for NBA hopefuls at a time when the NBA consisted of only eight teams. The EBL was also a haven for a number of players who had been banned from playing in the NBA because of their participation in the game-fixing scandals that had rocked college basketball in 1951, players who performed at the very highest level of the game as it was played at that time, players like the legendary Bill Spivey, Jack Molinas, and Sherman White, players way better than me but against whom I was able to hold my own—thus proving to myself that I was more than just a hotshot in the small world of Ivy hoops.

My seminar grades improved with each semester as I learned more about why I was where I was and what I was supposed to be doing there. Accordingly, my confidence rose, and my fellowship stipend was restored to a respectable level. By the time of the Man Ray exhibition, I’d been at Princeton for eight years, and I was more than ready to move on. Which I did, holding academic positions at a couple of places starting with UMass, in the process casting about intellectually while mostly doing teaching and writing—some art criticism, some art history, even a history of rock music published by Oxford University Press—until 1974 when, instead of tenure, I was offered the directorship of the Rose Art Museum. I knew virtually nothing about running a museum—museology didn’t even exist when I was in school—so I learned on the job and, as I did, it gradually dawned on me that I’d absorbed aspects critical to my new position when I was still at Princeton. Through my dissertation project, I had been introduced to working with living artists, I got a taste of how much I enjoyed and found meaning in that, and I subsequently learned I was pretty good at it and that it was central to my personal and professional identity. From its opening in 1961, the Rose Art Museum was known as a museum of the art of our time, of living art, and I made it even more so by emphasizing the artists who made that art. So it came to be that I was in a productive place, and an especially right place for me, which, for part of me, was enormously satisfying, though another part of me felt as though I had spent more than a decade circling back to where I started. So I wondered: How come it had taken me so long to figure my self out, and how long would it take to know more fully my self in each moment of the ongoing present.

But those are the questions we all live with, aren’t they, the questions that signal our humanness in modern experience, the questions that our modern, living art is made to lay bare and address? And because our selves are ever evolving via new encounters with one another and with our shared world, those are the questions we’ll continue to ask, knowing that they’ll take as long to answer as they take—as any artist will tell you.

Carl Belz is Director Emeritus of the Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University.

My first encounter with the museum profession had me writing a few paragraphs for the brochure of a modest Man Ray exhibition at the Princeton University Art Museum in the spring of 1963. I’d earned my doctorate earlier that year with a dissertation on Man Ray’s contribution to Dada and Surrealism and, armed with a BA, MFA and PhD, all from Princeton, I was about to set off to my first teaching job, at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst.

I came upon Man Ray through surveys of Dada and Surrealism I read while preparing for my qualifying examinations during spring semester 1962. He was mentioned chiefly as the lone American participant in those international movements, initially in New York, where he became friends with Marcel Duchamp following the 1913 Armory Show, and then in Paris, where he moved in 1921; and he was invariably represented by the two readymade objects that remain most closely associated with his signature: the flatiron with the nails on its surface—called “The Gift”—and the metronome with its attached photo of a human eye—called “Indestructible Object.” On the lookout for a dissertation topic throughout that semester, I began to think Man Ray might be my ticket, and I was encouraged to pursue that possibility when mentor Robert Rosenblum agreed to be my adviser on the project.

Digesting the scant literature on Man Ray that existed in 1962 required little time and effort but didn’t take me very far toward building a thesis. For that, I needed primary source material, which meant going to Paris for a month, visiting with Man Ray at his studio three or four times a week, seeing work both old and new, talking at length with him about his art and artistic thought, collecting and notating images of paintings, drawings and objects provided by the Man himself and, for much of the rest of the time, making copious notes for future reference. Throughout the process, Man Ray was fully and wonderfully accommodating. Along with all of the above, he sort of took me under his personal wing, loaning me old exhibition announcements and brochures to study, occasionally inviting me to accompany him on errands around town—we ran into Yves Klein one morning—taking me to lunch a few times and, shortly before I was scheduled to return home, showing me a little snapshot that I was unaware he’d taken in which I could be seen sitting on a couch in his studio, surrounded by objects of his making, among them the memorably cosmic painting of a woman’s lips called “Observatory Time, The Lovers” and, nearby, his early mobile comprised of readymade coat hangers called “Obstruction.” I naturally coveted the photograph to document my experience but, unable to summon the audacity to ask for it, I was fully content to return home with its memory—along with what I felt were the makings of a doctoral dissertation.

|

| Man Ray, Observatory Time, The Lovers, Oil on canvas, 1936. |

|

| Man Ray, Obstruction, 1961 (replica of the 1920 original), Mixed media, Dimensions variable. |

|

| Photograph of Carl Belz by Man Ray, Paris, 1962, 5-1/2 by 3-1/2 inches |

For instance, I didn’t go to Princeton to prepare for advanced study in the history of art, I went to Princeton to play ball and prepare for medical school. And I did pretty well on both fronts. I was a career .300 hitter in baseball, while in basketball I helped lead our freshman team to an undefeated season (freshmen weren’t permitted to play varsity in those days), averaged double-doubles (points and rebounds) for my three-year varsity career, shot my way into the elite 1,000 point club, set that single game rebounding record I told you about in an earlier Flashback, was twice named to the starting five of the All-Ivy team, captained Princeton to a share—with Dartmouth—of the Ivy League championship in my senior year, and only once got ejected from a game (against Harvard, for fighting, grrr). In the classroom, I aced organic chemistry in my sophomore year, then became a biology major, was admitted to medical schools at Columbia University and the University of Pennsylvania in the spring of my senior year, decided on Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, and set my sights on moving to New York.

|

| The Princeton varsity basketball team (minus one) for the 1956-57 season, with Carl Belz 3rd from the left, Sports Illustrated, December 8, 1997. |

Little did I know what I was getting into. I thought graduate study brought together a small group of people who, like me, had been blown away by art and would be spending large chunks of time talking about how great Titian and Velasquez and Pollock were. No. We were not there to learn and discuss the history of art per se—it was assumed we had already done that as undergraduates and needed only to fill in a course here and there to complete our introduction to the spectrum of western art history—we were there to learn the methods of the art historical discipline via encounters with the scholarship in which those methods were embodied. Accordingly, instead of Titian, Velasquez, and Pollock, our role models became individuals like Alois Riegl, Erwin Panofsky, and Meyer Shapiro. It took me most of my first year to figure that out, as my grades sadly attested. I got a mere “pass” in my graduate seminars, adding up to an implicit suggestion that I think twice about continuing in the program. Fortunately, I was still too naïve to read that writing on the wall.

I was, however, fully able to grasp what the writing said about the financial situation I would face in my second year, when my fellowship would be reduced to tuition alone—it said I’d better find work pronto! That’s when my undergraduate experiences began to pay off. Based on the lab skills I’d learned in science courses, I landed a job with a small chemical research firm in town, which I worked fulltime during the summer of 1960 and was able to continue on a part time basis once the academic calendar resumed in the fall. By that time, I’d also earned a spot playing professional basketball on Saturday and Sunday nights—and earning $50 a game—for the Scranton Miners of the Eastern Basketball League, which served as a breeding ground for NBA hopefuls at a time when the NBA consisted of only eight teams. The EBL was also a haven for a number of players who had been banned from playing in the NBA because of their participation in the game-fixing scandals that had rocked college basketball in 1951, players who performed at the very highest level of the game as it was played at that time, players like the legendary Bill Spivey, Jack Molinas, and Sherman White, players way better than me but against whom I was able to hold my own—thus proving to myself that I was more than just a hotshot in the small world of Ivy hoops.

My seminar grades improved with each semester as I learned more about why I was where I was and what I was supposed to be doing there. Accordingly, my confidence rose, and my fellowship stipend was restored to a respectable level. By the time of the Man Ray exhibition, I’d been at Princeton for eight years, and I was more than ready to move on. Which I did, holding academic positions at a couple of places starting with UMass, in the process casting about intellectually while mostly doing teaching and writing—some art criticism, some art history, even a history of rock music published by Oxford University Press—until 1974 when, instead of tenure, I was offered the directorship of the Rose Art Museum. I knew virtually nothing about running a museum—museology didn’t even exist when I was in school—so I learned on the job and, as I did, it gradually dawned on me that I’d absorbed aspects critical to my new position when I was still at Princeton. Through my dissertation project, I had been introduced to working with living artists, I got a taste of how much I enjoyed and found meaning in that, and I subsequently learned I was pretty good at it and that it was central to my personal and professional identity. From its opening in 1961, the Rose Art Museum was known as a museum of the art of our time, of living art, and I made it even more so by emphasizing the artists who made that art. So it came to be that I was in a productive place, and an especially right place for me, which, for part of me, was enormously satisfying, though another part of me felt as though I had spent more than a decade circling back to where I started. So I wondered: How come it had taken me so long to figure my self out, and how long would it take to know more fully my self in each moment of the ongoing present.

But those are the questions we all live with, aren’t they, the questions that signal our humanness in modern experience, the questions that our modern, living art is made to lay bare and address? And because our selves are ever evolving via new encounters with one another and with our shared world, those are the questions we’ll continue to ask, knowing that they’ll take as long to answer as they take—as any artist will tell you.

Carl Belz is Director Emeritus of the Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University.

Saturday, August 6, 2011

Some Art News

By Charles Kessler

A couple of new galleries opened on the Lower East Side.

The Hole

312 Bowery (just above Houston)

212-466-1100

The Hole Gallery moved from a hole of a space on Greene Street in Soho to a relatively large and airy space in the Lower East Side. The gallery is run by Kathy Grayson, a former director of Deitch Project, and the gallery employees are nice, young, ambitious and willing to try new things. For example, their last show, FriendsWithYou, the art of the Miami duo Samuel Borkson and Arturo Sandoval III, included a pop-up store that sold Native Shoes, a footwear company that makes some pretty wild shoes.

Mulherin + Pollard Gallery

212-967-0045

The gallery is at the end of Freeman Alley, across from Salon 94, off of Rivington between Bowery and Chrystie Streets. You can also enter at 187 Chrystie Street, but Freeman Alley is much more interesting. They have a group show there now entitled Mundus Incognita, but as yet there’s nothing on their website about it or future shows.

In other news:

Today Roberta Smith has an excellent review of the Met’s Frans Hals exhibition; this in contrast to the disappointing New Yorker review by Peter Schjeldahl (you can get only an excerpt online). Unfortunately, Schjeldahl's reviews lately have been superficial, contradictory and, surprising for The New Yorker, sloppily written.

One of the many nice thing about the Hals exhibition is the comparison you can make between Hals's painting Malle Babbe and a student version of the same subject. It really gives you a sense of how good Hals is.

Via the Los Angeles Times I found out about a FREE iPad app that has breathtaking photos, live-action video and interviews of a series of dances Merce Cunningham choreographed for the nonprofit visual and performing arts journal 2wice. And did I say it was FREE?

While I’m on apps, the National Gallery, London has two — a very good free one with a couple of hundred photographs of their collection that can be downloaded HD directly into your iPhone or iPad photo album; and a great $1.99 one with almost 2000 photos. Here’s a sample; click to enlarge:

report from the Brussels-based art dealers’ federation Cinoa is going around the blogosphere. They found that art fairs and on-line art sales are taking over as the main source of revenue, and it’s hurting traditional galleries.

Another thing making the rounds is an article in The Art Newspaper about why art is getting bigger. They conclude: Commissioning and acquiring art has always been a way for the wealthy and powerful to affirm their position, taste, influence and money; and there is nothing new either about huge spaces to display it in.

Finally, this to lift your spirits: The New York Times went through their archives and came up with a series of photographs of kids playing in New York. It’s a joy to look at.

A couple of new galleries opened on the Lower East Side.

The Hole

312 Bowery (just above Houston)

212-466-1100

|

| July 21st, The Hole hosted “The History of American Graffiti” book-signing event featuring special guest TAKI 183. Photo from their blog, “Art From Behind." |

Mulherin + Pollard Gallery

212-967-0045

The gallery is at the end of Freeman Alley, across from Salon 94, off of Rivington between Bowery and Chrystie Streets. You can also enter at 187 Chrystie Street, but Freeman Alley is much more interesting. They have a group show there now entitled Mundus Incognita, but as yet there’s nothing on their website about it or future shows.

In other news:

Today Roberta Smith has an excellent review of the Met’s Frans Hals exhibition; this in contrast to the disappointing New Yorker review by Peter Schjeldahl (you can get only an excerpt online). Unfortunately, Schjeldahl's reviews lately have been superficial, contradictory and, surprising for The New Yorker, sloppily written.

One of the many nice thing about the Hals exhibition is the comparison you can make between Hals's painting Malle Babbe and a student version of the same subject. It really gives you a sense of how good Hals is.

|

| Detail, Frans Hals, Malle Babbe, 1633-35, Oil on canvas (Staatliche Museen, Berlin) |

|

| Detail, Style of Frans Hals, Malle Babbe, mid-17th century, Oil on canvas, (Metropolitan Museum of Art) |

Via the Los Angeles Times I found out about a FREE iPad app that has breathtaking photos, live-action video and interviews of a series of dances Merce Cunningham choreographed for the nonprofit visual and performing arts journal 2wice. And did I say it was FREE?

|

| From 2wice's Merce Cunningham iPad App |

report from the Brussels-based art dealers’ federation Cinoa is going around the blogosphere. They found that art fairs and on-line art sales are taking over as the main source of revenue, and it’s hurting traditional galleries.

Another thing making the rounds is an article in The Art Newspaper about why art is getting bigger. They conclude: Commissioning and acquiring art has always been a way for the wealthy and powerful to affirm their position, taste, influence and money; and there is nothing new either about huge spaces to display it in.

Finally, this to lift your spirits: The New York Times went through their archives and came up with a series of photographs of kids playing in New York. It’s a joy to look at.

|

| 1977: In the mud at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, Neal Boenzi/The New York Times. |

Friday, August 5, 2011

EVERY THURSDAY: ¡Arriba! Music and Dance on the High Line

|

| Last Night, 9pm Check the High Line website for more events. |

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

A Few of My Favorite Things - Small East Side Museums

By Charles Kessler

Transportation Note: For the East Side museums, the best thing to do is start at the Neue Galerie (Fifth Avenue and 86th Street) and take the Fifth Avenue bus downtown to the other museums. They are never more than a few blocks away from a bus stop. It would require a lot of endurance to do all the East Side museums in one day; it’s possible, but not desirable.

Neue Galerie, 1048 Fifth Avenue (at 86th Street)

Warning: their website can be very slow sometimes.

Hours: Thursday - Monday, 11 am - 6 pm; (closed Tuesday and Wednesday)

Admission: $15 General; $10 Students and Seniors. The museum is free from 6 - 8 pm on the first Friday of every month.

Photography is only permitted on the ground floor and lower level of the building; you are not allowed to enter the museum with bottled water - they make you throw it away!

The Neue Galerie is devoted to early twentieth-century German and Austrian art and design. It is relatively new -- they opened on November 16, 2001 in a converted Fifth Avenue mansion, the former William Starr Miller House, a Louis XIII/Beaux-Arts structure. Happily they kept many of the historic details of the Miller House and added architectural and design elements from early twentieth-century Vienna. In addition to the museum, they also have a bookstore, design shop, and two Viennese cafés: Café Sabarsky and Café Fledermaus.

The Neue Galerie cafés are an important part of the experience of this museum. They are modeled after the Viennese cafés that served as important centers of intellectual and artistic life at the turn of the century and are outfitted with period objects including lighting fixtures by Josef Hoffmann and furniture by Adolf Loos. Viennese food is their specialty, and it’s superb, especially their pastries such as strudel and Linzertorte. There are usually long waits to get in, but it’s well worth it, especially Café Sabarsky.

Currently on view (only until August 8th) is an ambitious exhibition, Vienna 1900: Style and Identity,

that aims to: reveal a common thread running through the fine and decorative arts in turn-of-the-century Vienna: the redefinition of individual identity in the modern age. The show explores the newly-evolving attitudes about gender and sexuality, and it's especially interesting in that it includes clothing, accessories, and even a pornographic movie of the period.

This Schiele is actually one of the tamer drawings in the exhibition — after all, this is a family blog! Schiele, like many of his fellow artists, pushed the boundaries of what was permissible, and he was convicted for displaying indecent images where minors could have viewed them. This was a lesser crime than what he was originally accused of: kidnapping and sexually molesting a a fourteen-year-old girl who ran away from home and sought refuge with Schiele and his model Wally Neuzil.

One of my favorite works in the show, and it’s part of their permanent collection, is a self-portrait by the little-known Richard Gerstl. Little-known because Gerstl, at the age of 25, after a disastrous love affair with Schönberg’s wife, killed himself and destroyed most of his work. Fewer than 100 pieces survive.

And for Gustav Klimt lovers, I counted 10 paintings in the exhibition, many major ones, and 12 drawings.

The Frick Collection, 1 East 70th Street (at Fifth Avenue)

Hours: Tuesday - Saturday, 10:00 am - 6:00 pm; Sundays, 11:00 am - 5:00 pm.

Admission: $18 General; $15 Seniors; $10 Students. Pay what you wish Sundays 11:00 am - 1:00 pm.

Photography is not permitted.

The Frick is simply the BEST small museum in the country -- maybe the world! Visiting the Frick is like walking through the pages of Janson’s History of Art (is this still used for Art History Survey classes?). They have some of the best art, by some of the best European artists, displayed under the best conditions — installed in the Henry Clay Frick mansion. The only problem is that people have found out about this treasure so it can get crowded. It's best to get there when it first opens.

They also have an excellent website with beautiful color, zoomable, photos of practically everything in their collection, and with detailed information about each work. They even provide an email address, info@frick.org, if you need additional information. If that’s not enough, Google Art Project has a virtual tour of the Frick and several high def photographs of the highlights of the collection. (The Frick also has a virtual tour on their own website.)

Here are some of my favorites:

Okay, these paintings are almost silly in their romanticism, and I think Rembrandt at least was having some fun with the idea, but they’re also two of the great painterly paintings in the country.

The Frick has three of the thirty-five paintings now accepted as being by Vermeer. (The Met has five, the showoffs, but the Frick’s are better.)

And then there’s this:

Tip: Most of the time you’re allowed to sit on some of the plush chairs in the Living Hall, a peaceful and intimate room even when the museum is crowded. I love to doze off there because, for a few seconds after I wake up, I feel like I’m in paradise.

Asia Society Museum, 725 Park Avenue (at 70th Street)

Hours: Tuesday - Sunday, 11:00 am - 6:00 pm.

Admission: $10.00 General; $7.00 Seniors; $5 Students; free for persons under 16.

Admission is free on Fridays 6:00 pm to 9:00 pm.

Photography and electronic recording of any kind are not permitted anywhere in the building.

The museum is an uninteresting modern building, but at least it doesn’t intrude on the art.

Their claim to fame is the Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller Collection which is considered one of the great collections of Asian art in the United States even thought there are fewer than 300 pieces.

exhibition of photographs -- 227 relatively large ones, hung salon style, that the popular contemporary Chinese artist Ai Weiwei took from 1983 - 1993 when he was living in the East Village. The photographs are interesting for its documentation of that period, but they are little more than snapshots blown up, except maybe from 1990 onward where Ai Weiwei seemed to be exploring the medium a bit more.

The museum is in the process of installing a long-delayed exhibition of Buddhist art from Pakistan (opens August 9th).

The Morgan Library & Museum. 225 Madison Avenue (at 36th Street)

Hours: Tuesday - Thursday, 10:30 am - 5 pm; Friday, 10:30 am - 9 pm; Saturday, 10 am - 6 pm; Sunday, 11 am - 6 pm

Admission: $15 General; $10 Children, Seniors and Students. Free on Fridays, 7 pm - 9 pm.

Photography is not allowed except for the ground-floor public spaces.

The old Morgan Library and Museum, before the 2006 Renzo Piano expansion and renovation, was a Mecca for connoisseurs of drawing. Almost every time I went I would overhear educated and intelligent discussions about the drawings on view. Not anymore. What’s surprising is I don’t think attendance has increased since the renovation, at least not in my experience. I don’t know the numbers, but the place sure looks empty every time I’ve been there.

The Renzo Piano expansion and renovation added a lot: a nice welcoming entrance on Madison Avenue, two restaurants, greater handicapped accessibility, a beautiful new performance hall (see photo below), a better reading room, and better storage for the collections.

They claim to have doubled the amount of exhibition space, but it really doesn’t seem like that. In any case, typical of museum expansions in the last few years, there’s a lot of what I think of as wasted space — space devoted to a soaring glass atrium, an expansive lobby, a large museum store and two (!) restaurants. MoMA is the prime example, but it’s also true of most other museum expansions.

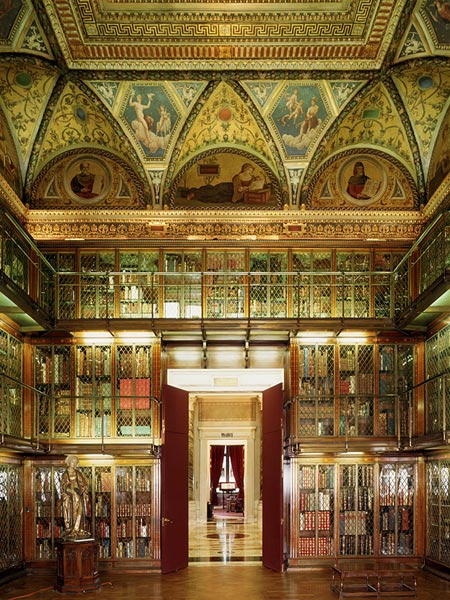

Do not not miss seeing the original Morgan Library. Even though it's connected to the modern addition, it’s a little hard to find. Ask one of the guards for directions. The Library is a palazzo-like structure built between 1902 and 1906. It was designed by Charles Follen McKim to serve as the private library of financier Pierpont Morgan, and it's pretty spectacular.

Here are some of my favorites works from the permanent collection that are currently on view in the old Morgan Library:

They also have a mind-boggling collection of original manuscripts including:

the sole surviving manuscript of John Milton's Paradise Lost, transcribed and corrected under the direction of the blind poet; Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s "autograph manuscript" of the Haffner Symphony; Charles Dickens's manuscript of A Christmas Carol; Henry David Thoreau's journals; Thomas Jefferson's letters to his daughter Martha; and manuscripts and letters of Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, Lord Byron, Wilkie Collins, Albert Einstein, John Keats, Abraham Lincoln and John Steinbeck.

Transportation Note: For the East Side museums, the best thing to do is start at the Neue Galerie (Fifth Avenue and 86th Street) and take the Fifth Avenue bus downtown to the other museums. They are never more than a few blocks away from a bus stop. It would require a lot of endurance to do all the East Side museums in one day; it’s possible, but not desirable.

Neue Galerie, 1048 Fifth Avenue (at 86th Street)

Warning: their website can be very slow sometimes.

Hours: Thursday - Monday, 11 am - 6 pm; (closed Tuesday and Wednesday)

Admission: $15 General; $10 Students and Seniors. The museum is free from 6 - 8 pm on the first Friday of every month.

Photography is only permitted on the ground floor and lower level of the building; you are not allowed to enter the museum with bottled water - they make you throw it away!

|

| Installation view, Vienna 1900: Style and Identity, Neue Galerie |

|

| Cafe Sabarsky, Neue Galerie. |

Currently on view (only until August 8th) is an ambitious exhibition, Vienna 1900: Style and Identity,

that aims to: reveal a common thread running through the fine and decorative arts in turn-of-the-century Vienna: the redefinition of individual identity in the modern age. The show explores the newly-evolving attitudes about gender and sexuality, and it's especially interesting in that it includes clothing, accessories, and even a pornographic movie of the period.

|

| Egon Schiele (1890-1918), Reclining Semi-Nude, 1911, Watercolor, gouache, and pencil (Private Collection) |

One of my favorite works in the show, and it’s part of their permanent collection, is a self-portrait by the little-known Richard Gerstl. Little-known because Gerstl, at the age of 25, after a disastrous love affair with Schönberg’s wife, killed himself and destroyed most of his work. Fewer than 100 pieces survive.

|

| Richard Gerstl, Self-Portrait in Front of a Stove, 1907, Oil on canvas on board, 27 x 21 ½ inches (Neue Galerie, New York). |

The Frick Collection, 1 East 70th Street (at Fifth Avenue)

Hours: Tuesday - Saturday, 10:00 am - 6:00 pm; Sundays, 11:00 am - 5:00 pm.

Admission: $18 General; $15 Seniors; $10 Students. Pay what you wish Sundays 11:00 am - 1:00 pm.

Photography is not permitted.

The Frick is simply the BEST small museum in the country -- maybe the world! Visiting the Frick is like walking through the pages of Janson’s History of Art (is this still used for Art History Survey classes?). They have some of the best art, by some of the best European artists, displayed under the best conditions — installed in the Henry Clay Frick mansion. The only problem is that people have found out about this treasure so it can get crowded. It's best to get there when it first opens.

|

| Screen shot of the Living Hall from the Frick virtual tour. |

|

| Screen shot of the West Gallery from the Frick virtual tour. |

Here are some of my favorites:

Okay, these paintings are almost silly in their romanticism, and I think Rembrandt at least was having some fun with the idea, but they’re also two of the great painterly paintings in the country.

The Frick has three of the thirty-five paintings now accepted as being by Vermeer. (The Met has five, the showoffs, but the Frick’s are better.)

|

| Johannes Vermeer, Officer and Laughing Girl, c. 1657, oil on canvas (lined), 19 7/8 x 18 1/8 in. (Henry Clay Frick Bequest, Accession number: 1911.1.127). |

|

| Piero della Francesca, St. John the Evangelist, c. 1454-1469, tempera on poplar panel, 52 3/4 x 24 1/2 inches (Purchased by The Frick Collection, 1936, Accession number: 1936.1.138). |

Asia Society Museum, 725 Park Avenue (at 70th Street)

Hours: Tuesday - Sunday, 11:00 am - 6:00 pm.

Admission: $10.00 General; $7.00 Seniors; $5 Students; free for persons under 16.

Admission is free on Fridays 6:00 pm to 9:00 pm.

Photography and electronic recording of any kind are not permitted anywhere in the building.

The museum is an uninteresting modern building, but at least it doesn’t intrude on the art.

|

| Exterior, Asia Society Museum |

exhibition of photographs -- 227 relatively large ones, hung salon style, that the popular contemporary Chinese artist Ai Weiwei took from 1983 - 1993 when he was living in the East Village. The photographs are interesting for its documentation of that period, but they are little more than snapshots blown up, except maybe from 1990 onward where Ai Weiwei seemed to be exploring the medium a bit more.

The museum is in the process of installing a long-delayed exhibition of Buddhist art from Pakistan (opens August 9th).

The Morgan Library & Museum. 225 Madison Avenue (at 36th Street)

Hours: Tuesday - Thursday, 10:30 am - 5 pm; Friday, 10:30 am - 9 pm; Saturday, 10 am - 6 pm; Sunday, 11 am - 6 pm

Admission: $15 General; $10 Children, Seniors and Students. Free on Fridays, 7 pm - 9 pm.

Photography is not allowed except for the ground-floor public spaces.

The old Morgan Library and Museum, before the 2006 Renzo Piano expansion and renovation, was a Mecca for connoisseurs of drawing. Almost every time I went I would overhear educated and intelligent discussions about the drawings on view. Not anymore. What’s surprising is I don’t think attendance has increased since the renovation, at least not in my experience. I don’t know the numbers, but the place sure looks empty every time I’ve been there.

The Renzo Piano expansion and renovation added a lot: a nice welcoming entrance on Madison Avenue, two restaurants, greater handicapped accessibility, a beautiful new performance hall (see photo below), a better reading room, and better storage for the collections.

|

| Gilder Lehrman Performance Hall, The Morgan Library & Museum. |

|

| The Morgan Library & Museum’s new lobby. |

|

| Eastroom - Pierpont Morgan's library |

|

| Westroom - Pierpont Morgan's study |

|

| Hans Memling, Portrait of a Man with a Pink, ca. 1475, Tempera on panel, 10 3/4 x 15 inches (Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1907; AZ073). |

|

| Pietro Vannucci, called Perugino, Madonna and Saints Adoring the Christ Child, ca. 1500, Tempera on wood, 34 1/2 x 28 3/8 inches (Purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911; AZ066). |

the sole surviving manuscript of John Milton's Paradise Lost, transcribed and corrected under the direction of the blind poet; Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s "autograph manuscript" of the Haffner Symphony; Charles Dickens's manuscript of A Christmas Carol; Henry David Thoreau's journals; Thomas Jefferson's letters to his daughter Martha; and manuscripts and letters of Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, Lord Byron, Wilkie Collins, Albert Einstein, John Keats, Abraham Lincoln and John Steinbeck.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)