|

| Sydney Schiff Dance Project, August 17, 2013, Socrates Sculpture Park. |

|

| Gleich Dancers, Selection from Speak Easy Secrets, Dance at Socrates, August 10, 2013. |

I've been seeing a lot of dance lately, and I've come to the conclusion that dance is magical in a way no other art form (except possibly opera) can duplicate. Real live people (okay, younger and thinner) fly, or are effortlessly lifted in the air as if they weigh nothing; and their movements are more graceful (even when they try to be awkward), and certainly more interesting, than ordinary people's. Sure, flying and all kinds of fantastic things happen in movies, but it's not live. In addition, a lot of dance is joyous and ebullient – something that hardly exists anymore in painting and sculpture, unfortunately.

Then there's Socrates Sculpture Park itself. In the early eighties it was an illegal dump – an abandoned four-acre wasteland. In 1986 the sculptor Mark di Suvero brought together a group of artists and people from the area to clean it up with the idea of making it into an informal community park and a place where sculptors could make and exhibit their art. When I first started going there in the late eighties, it was still pretty raw and didn't look much different from the photo below.

|

| Socrates Sculpture Park before it was developed. (Photo from the Socrates Sculpture Park website.) |

|

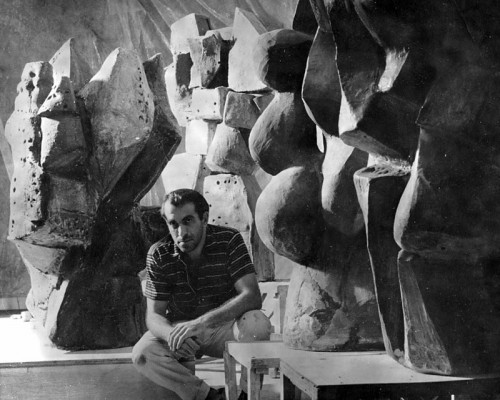

| Anthony Heinz May, one of the 2013 Emerging Artist Fellows, working on his sculpture. |

Details:

The address: 32-01 Vernon Boulevard at Broadway, Long Island City (Queens), NY 11106.

Directions: During the week both the Q and N trains will get you there, but on weekends ONLY the

N train goes there. Get off at the Broadway stop in Long Island City, Queens, and either walk eight blocks west on Broadway (toward the East River – 3/4 mile according to Google Maps, about a 15 minute walk) until it dead-ends at Vernon Boulevard, or take the Broadway bus which comes by about every 10 minutes.

Hours: Open every day from 10 am until sunset.

You can also easily go to the Noguchi Museum, only a block away on Vernon Blvd. at 33rd Road, and make a day of it.

|

| Isamu Naguchi Museum Garden. |

..jpg)