|

| Interior, Rose Museum. Photo: Mike Lovett |

Thursday, June 30, 2011

Monday, June 27, 2011

Saturday, June 25, 2011

Yes We Can!

|

| Last night in Sheridan Square, outside the Stonewall Inn. Photo credit: C.S. Muncy for The New York Times |

Sunday, June 19, 2011

Some Noteworthy Events and Reading Suggestions

By Charles Kessler

|

| Christine Goodman |

Click here for tickets.

They are only $15 in advance ($18 at the door) and Smith Street, where the theater/pub is located, is one of the liveliest and most interesting urban streets around.

Jersey City photographer Edward Fausty had a major exhibition of his otherworldly digital pictures of night scenes at the Hunderdon Art Museum. (For some reason I can’t make a hyperlink here -- you need to copy and paste the address: http://www.hunterdonartmuseum.org/past_exhibits/index.php#fausty.) It closed last week, but I believe it was important enough to at least document here. The subtle, glowing color and velvety surfaces make these some of the most painterly photographs I’ve ever seen. A better place to view this work online is Fausty’s website.

|

| Edward Fausty, House and Tree, Mt. Wilson Observatory, CA. (#3682), 2010, 25 x 34 inches |

The Times and the Star Ledger reviewed Nimbus, a Jersey City dance company, so you don’t need my input. Suffice to say that for less than 20 dollars you got to sit a few feet away from first-rate professional dancers performing some of the best of Martha Graham as well several new works choreographed for this group.

SOME READING SUGGESTIONS

Long-form articles, like those found in the New Yorker or The Atlantic, haven’t been completely obliterated from the web. In fact there seems to be a small revival, possibly thanks to such free apps as Read It Later and Instapaper that let you save the text of a web page for future offline viewing, and websites like Long Reads, Long Form and my favorite, The Browser, that recommend long-form articles. These sites are not automated news aggregators but are run by actual human beings (what will they think of next?) who select the work and provide brief summaries to help you decide if you’re interested in reading them.

Here are two examples of long-form articles I found via The Browser. Neither one is strictly about art, but both are brilliant and provide insight for the larger cultural picture.

The first is a review of The Anatomy of Influence by Harold Bloom, the prominent literary critic. Bloom said he wrote this book at the age of 80 “to say in one place most of what I have learned to think about how influence works in imaginative literature.” The review, by Sam Tanenhaus, the editor of the New York Times Book Review, not only summarizes Bloom's own overview of his thinking (no small achievement), but he puts Bloom in the context of twentieth-century literary criticism.

One might not need The Browser to find a New York Times book review, but what are the chances you’d come across this review in the online edition of the Israeli Haaretz Daily Newspaper?

|

| Ludwig Wittgenstein, Photographiert von Ben Richards unter Anleitung Wittgensteins, September 1947 in Swansea Quelle: Schwules Museum, Berlin © Wittgenstein Archive, Cambridge |

And a final bit of good news on the long-form article front: a new online book-review website has been launched, The Los Angeles Review of Books. They just published a comprehensive review by Ben Lerner of MoMA's Ab Ex show, and an extensive and insightful review by Robert Polito of Patricia Patterson: Here and There, an exhibition at the California Center for the Arts (until September 3, 2011).

|

| Patricia Patterson, The Conversation (Manny and Steve at the Table), 1990, casein on canvas, painted wood frame, 72 x 102 inches (Collection Maggie and Terry Singleton) |

...In the end, the legal implications of the decision are clear: yes, exotic dancing can count as art — but only if the dancers' "particular moves" are something they picked up in college.And this from The Observer, The Guardian: Van Dyck paintings unearthed by saleroom sleuth

...A London dealer has revealed the methods that have enabled him to attribute three unknown works to Charles I's court painter. ...Philip Mould, a British dealer who once bought a Gainsborough on eBay for £120, has proved his eagle eye once again with the find, which includes two paintings sold by Christie's last year as anonymous works.

|

| Anthony Van Dyck, Self Portrait, 1640, oil on canvas, oval 23 x 19 inches |

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

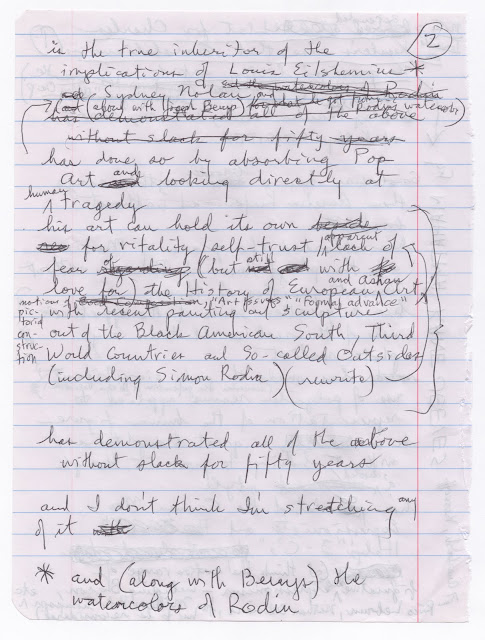

Mahatma Kane Jeeves on Charles Garabedian

Here's a response to my post on Charles Garabedian.The best way to view this is to click on each image to enlarge it, and click again to enlarge it even more.

|

| Page 1 - CLICK TO ENLARGE |

|

| Page 2 - CLICK TO ENLARGE |

|

| Page 3 - CLICK TO ENLARGE |

|

| Pages 4 & 5 - CLICK TO ENLARGE |

|

| Detail - Page 5 - CLICK TO ENLARGE |

Thursday, June 9, 2011

Curatorial Flashbacks #14: Barnet Rubenstein RIP

By Carl Belz

I recently rediscovered the obituary I wrote for Barney Rubenstein, a Boston-based painter whose work and whose friendship exceptionally enriched my life for many years prior to his death in 2002. It was written on the assumption that it would be published in The Boston Globe, but it was filed away when I learned of the Globe’s policy to write its own obituaries. Rereading it, I have been moved to share it—in the company of a few images of Barney’s pictures—in the hope of sparking an awareness of his achievement to an audience that ranges beyond the Back Bay.

.

Barnet Rubenstein, 1923-2002

Barnet Rubenstein, painter, teacher, raconteur, sports enthusiast, and beloved friend of countless members of Boston’s cultural community, died in his Brookline home on April 15, 2002, Patriots Day, Marathon Day, with the Yanks at Fenway wrapping up a four game series with the Olde Towne Team. Born and raised in Chelsea, Massachusetts, he would have been 79 on July 21.

Of all the things Barney was, he was first of all an artist, always making images. He drew cars and comic strip heroes for fun while at school in Chelsea, and for diversion he drew tanks and planes while serving in the U.S. Signal Corps during World War II. He then started to draw and paint in earnest, figures and interiors and still lifes, first at the Massachusetts College of Art in 1946-47, and then for five years at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts where he would later teach for more than three decades. He became practiced in the manner of Abstract Expressionism while living in Southern France for twelve years starting in 1953, but he drew and painted ocean liners and buses and racing ponies—he called them New York subjects—when he came back to the USA in 1965 and took up residence at the Chelsea Hotel in Gotham. After returning permanently to Boston in 1975, he spent the next twenty years imaging take-out food containers, cardboard boxes, jars of cookies, and arrangements of fruits and flowers, and he continued to draw and paint up to the very end—mostly the tree-lined paths where he regularly walked—despite a debilitating neurological condition that made it nearly impossible, physically, for him to draw or paint at all.

|

| Barnet Rubenstein, Calumet Rider and Jockeys, 1967, oil on canvas, 20 x 16 inches |

Like many artists of his generation, Barney could lovingly be said to have lived at times in a dream world untroubled by contradictions. He’d talk about making it in the Big Apple, though he didn’t have an entrepreneurial bone in his body. He’d describe series after series of ambitious pictures that he had in mind while working at a snail’s pace, as if time just didn’t matter. He’d be scheduled for a longed-for solo exhibition but would then want to postpone it because he wasn’t sure his current paintings were fully realized. But exposure and recognition came in spite of the endearingly mixed feelings he had about success: In numerous group exhibitions during the 1970s when realist-type painting enjoyed renewed attention, and theme shows began their ongoing ascendancy; in an eye-opening mid-career survey at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts in 1979; in a handful of radiant solo shows at the Alpha Gallery during the 1980s; and in a crowning retrospective at the Rose Art Museum in 1997 that celebrated four decades of his achievement. As a result, public and private collections throughout New England and elsewhere became homes for treasured paintings and drawings that in many cases had to be coaxed from Barney’s studio.

|

| Barnet Rubenstein, Grapes, Pear, Apple, 1984, pencil and colored pencil on paper, 10 1/4 x 15 1/2" private collection. |

Throughout his life—in his art, in his teaching, and in the stories he memorably told—Barney communicated a deep respect for art’s recent and distant past. In this he followed the model he learned as a student at the Museum School more than a half century ago, and he in turn gifted it to the generations of aspiring artists who studied with him, just as he gifted it to countless colleagues and friends, which was always with boundless generosity. He extended the same respect to the humble objects he painted—the fruits and flowers, the cookies and jars and boxes—patiently articulating each of them with nature’s life-giving light and attendant color. We know the pictures came about through painstaking effort and were hard to part with, but we don’t feel that effort when looking at them. We feel instead their joy and wonder, how they justify themselves by merely existing, and we in turn feel as though their maker was grateful simply for the opportunity to bring them into being. Such is the gift of art when it is practiced at its highest level, which is the way Barney practiced and gifted it, and a supreme gift it remains.

|

| Barnet Rubenstein, Sunflowers and a Rose, late 1990's, pencil and colored pencil on paper, private collection |

Carl Belz is Director Emeritus of the Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University.

Wednesday, June 8, 2011

Some Reading Suggestions

By Charles Kessler

Another relatively recent archeological discovery is radically changing the way we understand the evolution of civilization (see my post on the Cauvet cave paintings). Charles C. Mann summarizes some of the latest thinking in his National Geographic article about the Gobekli-Tepe Pillars of southern Turkey: We used to think agriculture gave rise to cities and later to writing, art, and religion. Now the world’s oldest temple suggests the urge to worship sparked civilization.

The Gobekli-Tepe Pillars are a Stonehenge-type structure but taller, more finished and much older (about 11,600 years old). One of the other interesting things about Göbekli Tepe is the builders got steadily LESS competent over the millennia. More photos can be found on the official Turkish site. (Scroll about halfway down for a text in English.)

Jonathan Jones of the Guardian suggests curators could learn something from the way Shakespeare is presented:

Theatres bring Shakespeare searingly alive time and again, so why are art galleries content to leave the old masters in their graves? ...why can't the custodians of great art make Rembrandt, Raphael and Rubens as immediate as actors and directors make Shakespeare?

Richard Dorent, the astute art critic for the London Telegraph, reviews the Musee Orsay's Manet exhibition. He compares Titian's Venus of Urbino with Manet's Olympia (see photos above):

...All this implies a new and more active relationship between the subject and the viewer. Titian’s goddess feigns indifference to our presence whereas Olympia sizes us up, takes our measure. One is immortal, beyond human reach; the other could be booked after a good lunch at the Jockey Club.

Alan Taylor of the Atlantic put together this breathtaking album of 38 NASA photos of the solar system.

In his article Adrift: Will the Whitney’s new home allow it to finally find happiness?, Jed Perl, The New Republic’s art critic, makes some good points about the expansion of most art museums:

.... What museums are really looking for is not more exhibition space, per se—and certainly not more space for under-appreciated aspects of the permanent collection—but rather for spaces large enough for a Richard Serra sculpture or a Matthew Barney installation. That stuff will impress potential donors, who couldn’t tell a Charles Demuth from an Arthur Dove if their lives depended on it.

Kyle Chayka, writing in the Hyperallergic art blog, has a rudimentary but good summary of Performance Art here including this serviceable definition:

...If we were to assign performance art a single defining characteristic, it would probably be the fact that a piece of performance art must be centered on an action carried out or orchestrated by an artist, a time-based rather than permanent artistic gesture that has a beginning and an end.

In addition, she provides a brief description of several iconic performances.

Chayka also has an excellent photo essay on the newly opened Section 2 of the High Line.

Update: The Guardian has an article today on the opening of Section 2 of the High Line. What's taking the Times so long?

Vanessa Thorpe of the Guardian/Observer goes out on a limb:

...The freshest art on the contemporary scene appears to have turned its back on the ironic jokes and personal confessions epitomised by Tracey Emin's notorious unmade bed and Damien Hirst's dead floating shark.

From her lips to God's ears!

Joanne Mattera has some suggestions for making artists' statements more effective. I still think the best advice is that unless you're really good at it, DON’T DO IT -- you could easily sound like a pompous ass.

Another relatively recent archeological discovery is radically changing the way we understand the evolution of civilization (see my post on the Cauvet cave paintings). Charles C. Mann summarizes some of the latest thinking in his National Geographic article about the Gobekli-Tepe Pillars of southern Turkey: We used to think agriculture gave rise to cities and later to writing, art, and religion. Now the world’s oldest temple suggests the urge to worship sparked civilization.

|

| Gobekli-Tepe-Pillars, southern Turkey. Photograph by Vincent J. Musi |

Jonathan Jones of the Guardian suggests curators could learn something from the way Shakespeare is presented:

Theatres bring Shakespeare searingly alive time and again, so why are art galleries content to leave the old masters in their graves? ...why can't the custodians of great art make Rembrandt, Raphael and Rubens as immediate as actors and directors make Shakespeare?

Richard Dorent, the astute art critic for the London Telegraph, reviews the Musee Orsay's Manet exhibition. He compares Titian's Venus of Urbino with Manet's Olympia (see photos above):

...All this implies a new and more active relationship between the subject and the viewer. Titian’s goddess feigns indifference to our presence whereas Olympia sizes us up, takes our measure. One is immortal, beyond human reach; the other could be booked after a good lunch at the Jockey Club.

Alan Taylor of the Atlantic put together this breathtaking album of 38 NASA photos of the solar system.

|

| NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) satellite captures an image of the Earth's moon crossing in front of the Sun, on May 3, 2011. |

.... What museums are really looking for is not more exhibition space, per se—and certainly not more space for under-appreciated aspects of the permanent collection—but rather for spaces large enough for a Richard Serra sculpture or a Matthew Barney installation. That stuff will impress potential donors, who couldn’t tell a Charles Demuth from an Arthur Dove if their lives depended on it.

Kyle Chayka, writing in the Hyperallergic art blog, has a rudimentary but good summary of Performance Art here including this serviceable definition:

...If we were to assign performance art a single defining characteristic, it would probably be the fact that a piece of performance art must be centered on an action carried out or orchestrated by an artist, a time-based rather than permanent artistic gesture that has a beginning and an end.

In addition, she provides a brief description of several iconic performances.

Chayka also has an excellent photo essay on the newly opened Section 2 of the High Line.

|

| Section 2 of the High Line. Photo: Kyle Chayka. |

Vanessa Thorpe of the Guardian/Observer goes out on a limb:

...The freshest art on the contemporary scene appears to have turned its back on the ironic jokes and personal confessions epitomised by Tracey Emin's notorious unmade bed and Damien Hirst's dead floating shark.

From her lips to God's ears!

Joanne Mattera has some suggestions for making artists' statements more effective. I still think the best advice is that unless you're really good at it, DON’T DO IT -- you could easily sound like a pompous ass.

Charles Kessler is an artist and writer, and lives in Jersey City.

Sunday, June 5, 2011

Chelsea and 57th Street Gallery Roundup

By Charles Kessler

Willem de Kooning, The Figure: Movement and Gesture, paintings, sculptures, and drawings, The Pace Gallery, 32. E. 57th (at Madison), until July 29th.

This is a museum-quality show, and beautifully installed too, especially the large two-sided drawings that are set into the wall. I don’t have anything to add to the extensive de Kooning literature, but I’m eager to find out what John Elderfield will come up with for his major (more than 200 works) de Kooning retrospective at MoMA this fall.

Picasso and Marie-Therese L’Amour Fou at Gagosian Gallery, 522 West 21st Street, until June 25th.

Another museum-quality show -- more than eighty paintings, drawings, prints, photographs and sculptures. It's work inspired by Marie-Therese, Picasso's young lover of the late twenties to 1940. This show, even more than the current Museum of Modern Art exhibition “Picasso: Guitars 1912-1914” (see posts here and here), not only showcases Picasso's preternatural creativity but demonstrates how he milked an invention for all it's worth.

Keith Haring at Gladstone Gallery, 530 West 21st (down the street from Gagosian’s Picasso show), until July 1st.

This show is a good reminder of how generous and fun Keith Haring was. Haring’s openings were lively parties, often with live music and all kinds of free stuff like posters, stickers and t-shirts. The three large paintings in this show (about 9' x 23' each) were created on stage during a series of Bill T. Jones dance performances in 1982 (the sounds of the mark-making serving as the musical accompaniment). I thought Haring’s sketchbooks (Manhattan Penis Drawings for Ken Hicks, 1978 and Untitled (Cityscapes), 1978), also on display, were even more inventive and funny. The gallery is selling a reproduction of the sketchbooks for only $10.

Donald Judd at David Zwirner Gallery, 525 and 533 West 19th, until June 25th.

The impersonal fabrication, radical minimalism and the use of non-art materials (anodized aluminum and tinted Plexiglas) are supposed to preclude preciousness, and until a decade or so ago they did. But I think we’re over the shock of this, the way we’re over the rawness of Impressionist paintings. This work no longer has the presence of non-art, so now preciousness becomes an issue. Ultimately I don’t think they are. Maybe they’re so elegant that they pass preciousness to go on to jaw-dropping gorgeousness.

Richard Tuttle, What’s the Wind, The Pace Gallery, 510 West 25th , until July 22nd.

Tuttle, like Judd, can come dangerously close to preciousness, albeit in a way as different from Judd as is conceivable because Tuttle’s work is always experienced as handmade. The fragility (or apparent fragility -- they could in fact be very durable, I suppose) makes them appear delicate; and the careful placement of elements sometimes feels a little arty. But he’s so good at it, and the work is so playful and inventive, that preciousness is avoided here as well. Besides, these are large sculptures, self-contained installations really, unlike most of his other work, and the greater size alone helps give them more power.

Tuttle is hugely influential on younger artists, as any tour of the LES galleries will demonstrate. I don’t know why this show isn’t receiving more attention.

Jasper Johns, New Sculpture and Works on Paper, Matthew Marks Gallery, 522 West 22nd, until July 1st

Johns, at the age of 81, is making some of most sensual work he ever made — something that he’s gotten away from in the last few years. Yet I still find this work as unnecessarily and annoyingly obscure (is he trying to muddy the waters?) as always.

William Kentridge: Other Faces at Marian Goodman Gallery, 24 West 57th (between 5th and 6th), until June 18th

Of all the big-time shows currently on view, this was my personal favorite. I’m always surprised at how many people never heard of him even though he’s had shows at major museums. Kentridge is a South African artist who makes animated films by using successive charcoal drawings that he photographs, erases, changes and photographs again — each drawing getting a quarter of a second to two seconds of screen time. As the film evolves, there’s a sense of the passage of time like vestiges of a fading memory. And unlike conventional cel animation, Kentridge emphasizes the hand-drawn quality of the work — one is always aware of the artist’s presence. (Last Tuesday I went to an Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI) presentation and talk by Andrew Lampert, a film and video artist also involved with acknowledging the presence of the artist and with making work that's experienced as handmade. Maybe there’s something in the air. I hope so.)

Kentridge’s choice of subjects is inspired by his childhood in apartheid South Africa and the brutalized society left in its wake. His work is ambiguous, subtle and sometimes contradictory, but, unlike Johns, there’s a reason for it. As Kentridge said when asked (in a very good interview with Lillian Tone) why his work had become more associative and ambiguous: “Things that seemed more certain eight years ago seem less certain now.”

Charles Kessler is an artist and writer, and lives in Jersey City.

|

| Installation view: Willem de Kooning, The Figure: Movement and Gesture, paintings, sculptures, and drawings, The Pace Gallery. |

This is a museum-quality show, and beautifully installed too, especially the large two-sided drawings that are set into the wall. I don’t have anything to add to the extensive de Kooning literature, but I’m eager to find out what John Elderfield will come up with for his major (more than 200 works) de Kooning retrospective at MoMA this fall.

|

| Pablo Picasso, Femme nue dans un fauteuil rouge (1932) Photo: © Tate, London 2011/Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery |

Another museum-quality show -- more than eighty paintings, drawings, prints, photographs and sculptures. It's work inspired by Marie-Therese, Picasso's young lover of the late twenties to 1940. This show, even more than the current Museum of Modern Art exhibition “Picasso: Guitars 1912-1914” (see posts here and here), not only showcases Picasso's preternatural creativity but demonstrates how he milked an invention for all it's worth.

|

| Installation view: Keith Haring, Gladstone Gallery |

This show is a good reminder of how generous and fun Keith Haring was. Haring’s openings were lively parties, often with live music and all kinds of free stuff like posters, stickers and t-shirts. The three large paintings in this show (about 9' x 23' each) were created on stage during a series of Bill T. Jones dance performances in 1982 (the sounds of the mark-making serving as the musical accompaniment). I thought Haring’s sketchbooks (Manhattan Penis Drawings for Ken Hicks, 1978 and Untitled (Cityscapes), 1978), also on display, were even more inventive and funny. The gallery is selling a reproduction of the sketchbooks for only $10.

|

| Donald Judd, Untitled (Menziken 89-6), 1989, anodized aluminum, clear and blue with blue Plexiglas, 39 x 79 x 79 inches (Judd Art copyright Judd Foundation) |

The impersonal fabrication, radical minimalism and the use of non-art materials (anodized aluminum and tinted Plexiglas) are supposed to preclude preciousness, and until a decade or so ago they did. But I think we’re over the shock of this, the way we’re over the rawness of Impressionist paintings. This work no longer has the presence of non-art, so now preciousness becomes an issue. Ultimately I don’t think they are. Maybe they’re so elegant that they pass preciousness to go on to jaw-dropping gorgeousness.

|

| Installation view: Richard Tuttle, "What's the Wind," Pace Gallery |

|

| Detail: Richard Tuttle, "What's the Wind," Pace Gallery |

Tuttle, like Judd, can come dangerously close to preciousness, albeit in a way as different from Judd as is conceivable because Tuttle’s work is always experienced as handmade. The fragility (or apparent fragility -- they could in fact be very durable, I suppose) makes them appear delicate; and the careful placement of elements sometimes feels a little arty. But he’s so good at it, and the work is so playful and inventive, that preciousness is avoided here as well. Besides, these are large sculptures, self-contained installations really, unlike most of his other work, and the greater size alone helps give them more power.

Tuttle is hugely influential on younger artists, as any tour of the LES galleries will demonstrate. I don’t know why this show isn’t receiving more attention.

|

| Jasper Johns, Untitled, 2007, Aluminum, 108x83x2 inches |

Johns, at the age of 81, is making some of most sensual work he ever made — something that he’s gotten away from in the last few years. Yet I still find this work as unnecessarily and annoyingly obscure (is he trying to muddy the waters?) as always.

|

| William Kentridge, Drawings for Other Faces, 2011, charcoal and colored pencil on paper, 65x35 inches |

Of all the big-time shows currently on view, this was my personal favorite. I’m always surprised at how many people never heard of him even though he’s had shows at major museums. Kentridge is a South African artist who makes animated films by using successive charcoal drawings that he photographs, erases, changes and photographs again — each drawing getting a quarter of a second to two seconds of screen time. As the film evolves, there’s a sense of the passage of time like vestiges of a fading memory. And unlike conventional cel animation, Kentridge emphasizes the hand-drawn quality of the work — one is always aware of the artist’s presence. (Last Tuesday I went to an Electronic Arts Intermix (EAI) presentation and talk by Andrew Lampert, a film and video artist also involved with acknowledging the presence of the artist and with making work that's experienced as handmade. Maybe there’s something in the air. I hope so.)

Kentridge’s choice of subjects is inspired by his childhood in apartheid South Africa and the brutalized society left in its wake. His work is ambiguous, subtle and sometimes contradictory, but, unlike Johns, there’s a reason for it. As Kentridge said when asked (in a very good interview with Lillian Tone) why his work had become more associative and ambiguous: “Things that seemed more certain eight years ago seem less certain now.”

Charles Kessler is an artist and writer, and lives in Jersey City.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)